Iranian Identity in the West: A Discursive Approach

Seyed Sadegh Haghighat

How would the proponents of Iranian identity in Western

countries be defined today? Is it

limited to those living within the “nation-state” called Iran, or does it also

encompass extra implications? Considering that the identity of Iranians in the

civilized countries is not well explained for a number of reasons such as less

information and poor theoretical frameworks, how could we understand the

proponents of Iranian identity (with regard to its deep historical roots) in the

West, i.e. Europe and the U.S.?

Identity has played a pivotal role in social

movements. In sociology and political science, the

notion of “social identity” is defined as the way that individuals label

themselves as members of particular groups (e.g., nation, social class,

subculture, ethnicity, gender, etc.). It is in this sense that sociologists and

historians speak of the national identity of a particular country, and feminist

theorists speak of gender identity. Identity, here, is regarded as a social

phenomenon, not as a philosophical one.[1] Symbolic Interactionism (SI) attempts to show how identity

can influence, and be influenced by, social reality at large.[2] Every identity is unfixed and in flux, and Iranian identity in Western

countries with its components (Iranian or national/Islamic/liberal and

socialist) has faced crisis. The relative weight to be given to each of these,

partially overlapping, elements in defining the Iranian national identity has

generated much controversy among the successive generations of modern

intellectuals in Iran, particularly since the last decades of the nineteenth

century when the question of national identity moved to the center stage of

political discourse. Secular intellectuals have relied on a romantic conception

of nationhood that considers language as the hallmark of the community and the

source of national identity. Whilst the duality of Iranian/Islamic is rooted in

the emergence of the Islamic empire and its expansion to other parts of the

world, the triple concept of Iranian/Islamic/modern (including liberal and

socialist) dates back to the Constitutional Movement (mashrūṭeh) of 1905.

Iranian identity

crisis originates from some historical paradoxes. First, the 2500 year old Iranian

culture has a dual influence: a deep national heritage which shapes a social

imaginary on the one hand, and an authoritarian and political culture on the other.

Secondly, Islamic culture was merged into an Iranian one, but in practice there

were a lot of difficulties. The Safavid dynasty (1502- 1736) offered Shi-ite

Islam as the main pillar of Iranians’ collective identity. Thirdly, liberal

ideology as the hegemonic discourse in Europe and the U.S. penetrated into Iranian

culture especially in recent centuries. It goes without saying that this factor

is more influential for Iranians residing in Western countries. Finally and

most importantly, socialist culture from the communist countries, especially

from the Soviet Union , affected the non-harmonized

Iranian culture. This new culture transferred new signifiers, like the notion

of revolution, into the traditional and religious culture of Iranians.

The left, i.e. the socialist, signifiers made Iranian culture more complicated,

specifically when these signifiers transferred to Islamism as a new discourse

in 1960s. The Soviet Union collapsed in 1989, however, it had already left its

influence on political Islam in Iran, at least in the reading of ‘Ali Shari‘ati

and MKO[3].

Although the Islamic government in Iran has defined its principles on political

Islam, Iranians incline towards cultural Islam.[4]

Establishing Islamic government is considered the principal goal of political

Islam (Islamism), while Iranians live with their religion as a “culture”. The

Revolution in 1979, influenced by the socialist discourse, tried to intensify

Islamic aspects of the Iranian culture and to marginalize modern ones. Michel

Foucault called the Islamic revolution a postmodern one, and he was right when

he called it an anti-modern movement. However, it can not be considered a

postmodern one since it returned to Islamic and pre-modern principles. The more

Iranians (in the West) are distanced from 1979, the more their identity becomes

complicated. The Islamic Revolution brought cultural preoccupations to the

forefront of deliberations among scholars of Iranian studies. Motahhari’s view

on the collaboration between Iran and Islam[5]

on the one hand, and Doustar’s dīn-khū’ī[6]

(religious temperament) on the other hand demonstrate diverse and insufficient

endeavor to identify Iranian identity. Significantly, these

deliberations not only lack harmony in themselves but produce a chasm between

the four mentioned proponents of contesting views of Iranian national identity.

It is argued here that discourse

as a method can explain the characteristics of Iranians in first world

countries. Identity is shaped based on the other. But who is the other

of Iranian identity in the west? The point is that Iranian Identity crisis originates

from different sources of the self and their other. They do not know

exactly if their other is non-Iranian, non-Muslim, non-Shii-te, or

non-political Islam. Because I have addressed “Iranian Identity” in general in

an earlier work,[7] in

this essay I will concentrate on the identity crisis of Iranians in Western

countries. To discuss Iranian identity, this article draws on the insights of discourse

theory of Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe. The post-modernists render

problematic the traditional model of history as the “study of the past as it

was.” Meanwhile, Eric J. Hobsbawm and Benedict Anderson argue that nation is

neither natural nor eternal; that national identity is an assortment of “invented

traditions”; that nationalism is nothing more than a cultural artifact, that is

invented by collective imagination; and that nationality is more rooted in

subjective beliefs than objective realities.[8]

They argue that the basic assumptions historians make about the past are more

often than not ideological constructions; that historians are bounded within

their own cultural identities; that the nature of history is discontinuous; and

that historical “knowledge” is a form of discourse. Moreover, they claim that

subjective identity is itself a myth, a construct of language and society. In other words, national identity and

consciousness neither is inbred biologically nor transcendent but rather

manufactured.[9] According

to Bayat-Philipp: “The different expressions of Iranian national consciousness

today, be they secular or religious, reveal a similar tendency to conceive the

present as insubstantial and imperfect in comparison with the past.”[10]

Discourse as a

Method

Every

theory may engage some methods.[11]

In their

book, Jorgensen and Phillips talk about Discourse Analysis as

Theory and Methods. [12] According to them, “Discourse analysis” as a

method is the analysis of patterns identified in discourse as a theory. While Norman

Fairclough made a bridge between social studies and linguistics in his

discursive analysis, Laclau and Mouffe attempted to employ Foucault’s genealogy

in politico-social issues. In this article, I try to show the relationship

between text and context as Fairclaugh does. Furthermore, I will use some

statistics to confirm the idea developed here. As David Howarth puts it, we can

utilize discourse theory as a method: “Laclau and Mouffe oppose traditional

conceptions of social conflict in which antagonisms are understood as

the clash of social agents with fully constituted identities and interests. Hegemonic practices are important to Laclau and Mouffe’s

political theory of discourse, as they are an exemplary form of political

practice, which involves the linking together of different identities and

political forces into a common project, and the creation of new social orders

from a variety of dispersed elements. Their aim is thus to affirm the meaningfulness of

all objects and practices; to show that all social meaning is contingent,

contextual and relational; and to argue that any system of meaning relies upon

a discursive exterior that partially constitutes it. They challenge the closure of the linguistic

model, which reduces all elements to the internal moments of a

system. This implies that every social action simply repeats an already

existing system of meanings and practices, in which case there is no

possibility of constructing new nodal points that partially fix meaning,

which is the chief characteristic of an articulatory practice”.[13]

Laclau and Mouffe call articulation any practice establishing a

relation among elements such that their identity is modified as a result of the

articulatory practice. The structured totality resulting from the articulatory

practice, they call discourse.[14]

In the terms of their theory, the discourse establishes a closure, a

temporary stop to the fluctuations in the meaning of the signs.[15]

Foucault writes: “I am supposing that in every society the production of

discourse is at once controlled, selected, organized and redistributed

according to a certain number of procedures.”[16]

One of the best employments of

discourse as a theory and method is Edward Said’s analysis of colonialism. At

times he emphasizes a linguistic analysis as a methodology, the type similar to

that found in linguistic departments. His Orientalism, broadly speaking,

is a critical analysis of colonial ideology in Western literary texts. Said’s

unimaginably deep knowledge of literary texts, colonial history, geopolitics,

his powerful and yet accurate language, and most importantly his critical

reading of classic literary texts have made it an influential scholarly book

which impacts not only contemporary studies on the Middle East but it sets a

framework for critical works in post structuralism, anti-colonialism, and

anti-imperialism. Having a broad notion of CDA as an approach, “Orientalism”

can be classified as a “CDA study” in deconstructing and analyzing how a macro

ideology – Orientalism - has been incorporated into literary texts. Said, of

course, considers the crucial element in the proliferation of the ideology

differently from what is referred to as “discourse” among CDA researchers. He

considers language as one element of such hegemonic characterization. He argues

that; “Orient is an idea that has a history and a tradition of thought,

imaginary, and vocabulary that have given it reality and presence in and for

the West.” [17]

In short, discourse analysis can explain Iranian identity very well,

since it is formed by Iranian/Islamic/liberal and socialist discourses based on

non-essentialism. Being influenced by different sources, the identity of

Iranians has changed during time. Therefore there is no unique identity for

them.

Discourse and

Identity

Based on

the formal and relational theory of language that Saussure advocates, the identity

of any element is a product of the differences and oppositions

established by the elements of the linguistic system. He charts this conception

at the levels of signification - the relationships between signifiers and

signified - and with respect to the values of linguistic terms such as words.[18]

Essentialism alludes to a strong identity politics, without which there can

be no basis for political calculation and action. But that essentialism is only

strategic - that is it points, at the very moment of its constitution, to its

own contingency and its own limits.[19]

As discourses are relational entities whose identities depend on

their differentiation from other discourses, they are themselves dependent and

vulnerable to those meanings that are necessarily excluded in any discursive

articulation.[20] Identity

according to the discourse theory is a relative and unstable phenomenon, and

since there is no meta-discursive truth, every identity is produced in its

discourse. For Laclau and Mouffe, collective identity or group formation is

understood according to the same principles as individual identity. They reject

the position that collective identity (in Marxist theory, primarily classes) is

determined by economic and material factors. In such cases, the subject is overdetermined.

That means that he or she is positioned by several conflicting discourses among

which a conflict arises. For Laclau and Mouffe, the subject is always

overdetermined because the discourses are always contingent; there is no

objective logic that points to a single subject position. Subject positions

that are not in visible conflict with other positions are the outcome of

hegemonic processes. Therefore:

• The

subject is fundamentally split, it never quite becomes itself.

• It

acquires its identity by being represented discursively.

•

Identity is thus identification with a subject position in a discursive

structure.

•

Identity is always relationally organized; the subject is something

because it is contrasted with something that it is not.

•

Identity is changeable just as discourses are.

• The

subject is fragmented or decentred; it has different identities

according to those discourses of which it forms part.

• The

subject is overdetermined; in principle, it always has the possibility

to identify differently in specific situations. Therefore, a given identity is contingent

- that is, possible but not necessary.[21]

The

system is what is required for the differential identities to be constituted,

but the only thing - exclusion - which can constitute the system and thus make

possible those identities, is also what subverts them. Contexts have to be

internally subverted in order to become possible. The system is that which the

very logic of the context requires but which is, however, impossible. It is

present, if you want, through its absence. But this means two things. First,

that all differential identity will be constitutively split and undecidable.

Second, that although the fullness and universality of society is unachievable,

its need does not disappear: it will always show itself through the presence of

its absence. Finally, if that impossible object - the system - cannot be

represented but needs, however, to show itself within the field of

representation, the means of that representation will be constitutively

inadequate.[22]

Iranian identity

The word

“

The Samanid

dynasty was the first fully native dynasty to rule Iran since the

Muslim conquest, and led the revival of Persian culture. The first important

Persian poet after the arrival of Islam, Rudaki, was

born during this era and was praised by Samanid kings. Their successor, the Ghaznawids,

who were of non-Iranian Turkic origin, also became instrumental in the revival

of Persian. The culmination of the Persianization

movement was the Shahnameh

(1010 C.E), the national epic of Iran, written almost entirely in Persian by

Ferdowsi.

Language plays a pivotal role within the discourse of Iranian cultural

heritage. Many of

Of the various elements that constitute Iran’s cultural identity, four

have traditionally been judged the most salient. These include: (1) the

country’s pre-Islamic legacy, which took shape over a period of more than a

millennium, from the time of Achaemenians to the defeat of the last Persian

dynasty (the Sassanids) by the invading Arab armies in the middle of the

seventh century; (2) Islam, or, more specifically, Shi-ism, the religion of over

ninety percent of the country’s present-day inhabitants, with an

all-encompassing impact on every facets of Iranian culture and thought; (3) the

more diffuse bonds, fictive or real, established among peoples who have inhabited

roughly the same territory, with the same name, faced the same enemies,

struggled under the same despotic rulers and conquerors, and otherwise shared

the same historical destiny for over two millennia; and finally (4) the Persian

language, currently the mother tongue of a bare majority of the population, but

long the literary and “national language” in Iran (as well as in parts of

Afghanistan, Central Asia, and parts of the Indian subcontinent). The focus of

the present work is on the last of the above elements - i. e. the Persian

language - and its role in forming and sustaining Iranian national identity.

Maskub maintains that with the political and social changes that took place in

the closing decades of the nineteenth century, and with Persia’s increasing

contact with the West, the three social groups on which his analysis is focused

lost their significance as the principal guardians, practitioners, and

promoters of the Persian language. In all these capacities they were gradually

replaced by a new social group in the Iranian society, i.e., a secular

intelligentsia consisting of journalists, writers, poets, etc. According to

Boroujerdi, Maskub’s assertions and inferences are problematic for a number of

reasons. First, his view of language - epitomized

in such phrases as “refuge for the soul” and “substance of thought” - is more

romantic than factual. Scholars of Iranian studies should realize that while

language antedates and constructs subjectivity, it is never a “tabula rasa”.

Furthermore, while overemphasizing the role of language, Maskub underestimates

the function of imagination. Besides, language such previously critical factors

as race, religion, and common history no longer by themselves can be considered

the principal determinants of national identity. In the age of modernity,

“national identity” no longer should be conceived as something essential,

tangible, integrated, settled, and fundamentally unchanging. Language, after all, is a product of social

reality, and as such, the internal logic of cultural discourse must be situated

within the field of social practices and relationships. Although language

shapes culture, culture also shapes the development of language.[29]

It seems that Boroujerdi’s view is more compatible with the idea developed

here, since - based on discourse analysis - personal and collective identities

are becoming more self-reflexive, ambulatory, multiple, and fragile.

Farsi, as the official language, has become hegemonic for the

majority of Iranians. Although Persians form the majority of the population,

Iran is considered an ethnically diverse country. The point is that the

interethnic relations amongst minorities including Azeris, Kurds, Lurs, Arabs,

Baluchis, Turkmen, Armenians, Assyrians, Jews, and Georgians are more or less

harmonious. According to article 19 of the Iranian constitution, “All people of

Iran, whatever the ethnic group or tribe to which they belong, enjoy equal

rights; color, race, language, and the like, do not bestow any privilege”. In

fact, it explains the mystery of the failure of projects for the separation of

some provinces, like Khuzestan from Iran. Saddam Hussein had wrongly expected

the Iranian Arabs to join the Arab Iraqi forces in 1980 and win a quick

victory. According to the Seymour Hersh report in April 2006, US troops in Iran

were “recruiting local ethnic populations to encourage local tensions that

could undermine the regime”.[30]

Nayereh

Tohidi sees the settlement between the

Persian majority and the ethnic minorities under pressure, in ways that are

putting the country’s political future into question. First, minority politics

in Iran – whether related to gender, religion or ethnicity – in an age of

increasing globalization are influenced by a global-local interplay. Second, an

uneven and over-centralised strategy of development in

In brief, although the Iranian

language and customs may survive by and large amongst first generation Iranians

in the West, they would be weakened amongst the second generation. Children of

Iranians abroad do not have enough motivation to speak Farsi or to follow

Iranian customs, since they will lose their special symbolic meanings during

time.

The Duality of

Iranian/Islamic

The duality of Iranian/Islamic element in Iranian

identity emerged after the advent of Islam into Iran, however, it is one of our

main problems nowadays too. In Reza Shah’s era (1925-1945), this duality

intensified by quasi-modernism and secularism. Under his reign,

In contrast, the followers of the religious

approach believe that Iran’s pre-Islam history is the period of social

injustice and ignorance, and it was during the post-Islamic age, especially in the

Safavid period, that Iran achieved glory. They believe that the Iranian

identity is based on the Islamic culture and

civilization only. To demonstrate Iran-Islam cooperation, Motahhari puts less

importance on some elements like race and language.[37]

Two points should be noted here. First, anti-Islamism as a project ignores some

parts of history to magnify others. Second is the necessity of distinguishing Islam

as Muslim behavior in history (Islam 3) from Islam as holy texts (Islam 1) and

reading of Islam (Islam 2). The third sense of Islam does not necessarily imply

any sanctity. There is no reason to justify all Muslim behavior in any case

during time. Contingency and relativity of Iranian identity does not contradict

the holiness of Islamic texts, because here we talk about the Iranian/Muslim

identity as a social phenomenon.

From the Safavid era, Shi-ism became one of the formal components of

Iranian identity. In fact, Iranian identity depends on Shi-ism rather than

Islamic culture in general. Iranian identity would not be understood except with regard to the antagonism

between Shi-ism and Sunnism. Shi-ite

Muslims believe that the descendants from Muhammad through his daughter Fatima

Zahra and his son-in-law ‘Ali were the best source of knowledge of the Qur’an

and Islam, the most trusted carriers and protectors of Muhammad’s sunnah (traditions), and the most worthy

of emulation. The Safavid dynasty is of importance because of establishing Shi-ism

as the formal religion. Shah Ismail I initiated a religious policy to recognize

Shi-ite Islam as the official religion of the Safavid Empire, and the fact that

modern Iran remains an officially Shi-ite state is a direct result of Ismail’s

actions. He had to enforce official Shiism violently, since most of his

subjects were Sunni. But it is safe to say that the majority of the population

was probably genuinely Shiite by the end of the Safavid period in the 18th

century, and most Iranians today are Shi-ite, although small Sunni populations

do exist in that country. Following the establishment of Safavid religious

scholars (‘ulama) were invited to

Iran. This led to a wide gap between Iran and its Sunni neighbours which has

lasted to the present. Iranian identity in this period was partially shaped by the

antagonism with the Ottoman empire. Since there was no essence in the identity

of new government, signifiers of the Safavid discourse articulated around the

nodal point of Shah, whereas the Ottoman discourse’s nodal point was the Caliph.

Although the antagonism between Shi-ite and Sunnis developed in Safavid time, during

the early days of the Islamic Revolution, Ayatollah Khomeini endeavored to

bridge the gap between Shi-ites and Sunnis by forbidding criticisims of the

Caliphs who preceded ‘Ali — an issue that causes much animosity between the two

sects. Also, he declared it permissible for Shi-ites to pray behind Sunni imams.

The Tripartite Concept of Identity: Iranian/Islamic/Liberal

The Constitutional

movement at the turn of the twentieth century was a turning point for Iranians

to become familiar with modernity and liberalism. Iranian intellectuals were

the carriers of new ideologies. Hajjarian categorized them into three main

groups: the Non-traditionalists (from the Constitutional Movement to the 1940s),

the revivalists of tradition (from the 1940s to the Islamic Revolution),

and the synthesizers (in the Islamic republic era).[38]

Although his typology cannot explain all contemporary intellectual approaches,

it correctly shows that the first was modernist, while second which was

considered as the mainstream for political Islam was anti-modernist and traditionalist

in general. Because Iranian identity was not harmonized to deal with the duality of Iran/Islam, it encountered in

some ways a crisis in engaging with the triple concept of Iranian/Islamic/modern

(liberal and socialist).

In the nineteenth century Malkam Khan and Freemasonry’s “social order”

were based on ten principles: liberty, individual security, security of

properties, equal rights, freedom to thought and religion, freedom to speech,

freedom to write, and system of merits.[39]

While modernists (like Mostashar al-Dowleh)

and revivalists (like Na’ini) tried to justify the Iranian Constitution, which

was taken from the French , with Islamic teachings, conservatives (such as Fadlallah

Nuri and S. Ali Sistani) called constitutionalism as paganism! Mostashar al-Dowoleh

wrote in his letter to the monarch Mozaffar al-Din Shah: “regarding new

glorious progresses in Europe, Iran will necessarily accept

constitutionalism”.[40]

Meanwhile, Na’ini was more successful in justifying Constitutionalism based on

Sharia rules.[41] Tabataba’i

calls the Constitutional Movement the end of Iranian Middle Ages.[42]

Based on the discursive analysis, nothing was stable, and facing the

hegemonic modern discourse, the Iranian identity was in flux. Stressing “constitutionalism

based on shari‘a”, Nuri was hanged because of his opposition to the

Constitutional Movement, while it seems that his opponents like Na’ini tried to

synthesize constitutional and religious teachings! During the Constitutional

Movement, some modern concepts like liberty entered into the Iranian discourse,

but with some distortion since they could not articulate with other

signifiers in the new discourse. It was the same story in the reform period

between 1998-2006.

According to Laclau and Fairclaugh, every event (like the

Constitutional Movement, here) should be understood with regard to the primacy

of politics, power and language. Modernity may be recognized by a couple of

characteristics like humanism, rationalism, individualism, and technology. The

nodal point of liberalism, as the hegemonic discourse in the western modernity,

is liberty. Facing liberal culture, Iranians in Western countries compare this

modern culture with their homeland. First, they might try to synthesize the new

culture with Iranian and Islamic culture. The result would be a harmonic

synthesis or eclectic product. Then they might put one of the triple cultures,

or some aspects of one of them, aside. It is argued here that most Iranians

would somehow encounter crisis. The increasing number of migrants to Europe and

the U.S.A has increased the significance of the dilemma.

“The deterioration of Iranian political thinking”, according to

Tabataba’i, is rooted in a couple of tensions: between religion and culture,

between Iranians and the dictator governors, between Iranians and non-Iranians

(like Afghans and Turks), between national culture and foreign cultures,

between the political and the economic, and between Iranians and Iran. In the

last case, he points out the issue of emigration.[43]

In fact, there has been some migration to Europe and the United States by

Iranians who were studying overseas at the time of the revolution of 1979. The community

expanded predominantly in the early 1980s in the wake of the Iranian Revolution and the fall of the former

regime. The Iranian-American community has produced a sizable number of individuals notable in many fields,

including medicine,

engineering,

and business.

Migration and a brain drain to first

world countries are due to the acquisition by Iranians of managerial careers,

jobs in medicine and health, professional occupations, clerical jobs, jobs in

communication, commercial jobs, university students and financial jobs.[44]

About $ 9.2 billion fled from

• The Iranian foreign born are a

relatively new population whose migration to the United States

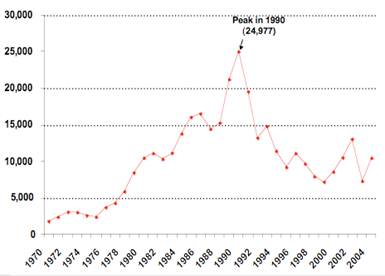

• Between 1980 and 1990, the number of

foreign born from Iran in

the United States

• The number of Iranians granted lawful

permanent residence peaked in 1990.

• From 1980 to 2004, more than one out

of every four Iranian immigrants was a refugee.

• There were about 280,000 Iranian born

in the United States

• Immigrants from Iran

• Between 1990 and 2000, the number of

Iranian foreign born increased over 34 percent.

Figure 1. Iranian-Born Immigrants

Admitted to the U.S., 1970-2004[46]

• During 2005, about 5,314 immigrant

visas were issued to Iranians.

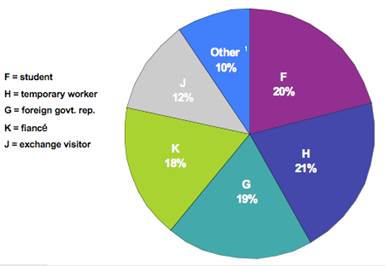

• In the last five years, the most

commonly issued nonimmigrant visas for Iranian nationals have been the student

(F), temporary worker (H), and foreign government representative (G) visas.

Figure 2.

Nonimmigrant U.S. Visas Issued to Iranian Nationals, 2000 to 2005[47]

• Three in every five Iranian

immigrants were naturalized US

• Over 90 percent of the Iranian

foreign born spoke a language other than English at home.

• The majority of the Iranian born had

a bachelor’s degree or higher.

• More than half of the Iranian

immigrant population was employed in management, professional, and related

occupations.

• In 2000, the median income for

Iranian-born males and females who were full-time, year-round workers was

$52,333 and $36,422, respectively. [48]

Iranian-Americans

are also prominent in academia. According to a preliminary list compiled by

ISG, there are more than 500 Iranian-American professors teaching and doing

research at top-ranked

The majority of Iranian

refugees are upper-middle class and others are wealthy. They have comparatively

liberal

political opinions and westernized lifestyles due in part to American

acculturation.

Iranian-Americans thus tend to be moderate in their practice of religion.[49]

Some practice Islam, however, this may diminish in the second generation. Will their dual identities as Americans and Iranian

Muslims be complementary or contradictory? Will they accept or reject the

Islamist program of changing the

Socialism and

Political Islam

Socialism,

as one of the modern ideologies, traveled to

Conspiracy theory, as one of the notions mentioned above, has roots in

the leftist ideologies which tried to form their identities in antagonism to

capitalism and colonialism. Iranian nationalist intellectuals and lay people

have developed an appetite for “conspiracy theories” in understanding their

history and particularly their collective traumas.[53]

According

to Edward Said: “‘imperialism’ means the practices, the theory, and the

attitudes of a dominating metropolitan centre ruling a distant territory;

‘colonialism’ which is always a consequence of imperialism, the implanting of

settlements on distant territory; As Michael Doyle puts it: ‘Empire is a

relationship, formal or informal, in which one state controls the effective

political sovereignty of another political society. It can be achieved by

force, by political collaboration, by economic, social, or cultural dependence.

Imperialism is simply the process or policy of establishing or maintaining an

empire.’”[54]

Political Islam in Iran has identified itself based on antagonism with Western

colonialism and imperialism’ conspiracies.

Antagonism with the West, especially with the U.S., has its roots in a

couple of events in Iranian history. First, during

Conclusion

Based on non-essentialism, Iranian

identity with its complex components (Iranian/Islamic/liberal/socialist) has been

shaped by antagonism with the other. Since the exteriority determines the

identity, it is contingent, decentred and in change. Iranian

identity should be understood with regard to ancient Iranian culture dating

back 2500 years, Islamic culture and its relationship with the first one,

facing modern civilization including liberalism and socialism, political Islam

(and the Islamic revolution) and the socialist influence on it, and antagonism

with the West. Similarly, Shaygan considers Iranian identity as a split and

juxtaposed one.[56] According

to Tabataba’i, because Iranians engage the “deterioration of political

thinking”, they have lost their ability to present new questions.[57]

Unlike the structuralist approaches to determinism, Laclau and Mouffe

place great importance on the concepts of subjectivity and agency in developing

their conception of discourse. They emphasize the way in which social actors

acquire and live out their identities, and stress the role of agency in

challenging and transforming social structures. Their perspective on the question of structure and

agency has resolutely attempted to find a middle path between the two critical

positions.[58] Since

Iranian identity in the West consists of four diverse elements, they face not

only opportunity, but threat. If the components are harmonized, Iranians might put

all the positive aspects of different cultures together, because tradition,

comprising religion, and modernity seem compatible. They need to rethink their

tradition critically, recognize modernity with its positive and negative

aspects, adapt it to their tradition and condition, and synthesize opposite

issues. Otherwise, if they try to choose the components arbitrarily or hastily the

result might be eclecticism and identity crisis. In this case, Iranians in Western

countries may need to develop a coordinated approach to tradition and modern

civilization. The difference between Iranians and westerners is that the latter

experienced modernity along with its foundations unconsciously, while Iranians

want to practice it intentionally without its foundations. Laclau and Mouffe

hold that “the logic of hegemony, as a logic of articulation

and contingency, has come to determine the very identity of the hegemonic

subjects. Unfixity has become the condition of every social identity. There is

no logical and necessary relation between socialist objectives and the

positions of social agents in the relations of production; and that the

articulation between them is external and does not proceed from any natural

movement of each to unite with the other. In other words, their articulation

must be regarded as a hegemonic relation”.[59] Iranians in the west should be aware of their Iranian identity, Islamic culture and modernity. Not

all history before Islam was an era of darkness and thus should be discarded,

nor was Islam a foreign, Arabic, imposed faith.[60]

The question of Iranian identity in Western

countries, especially of the second generation, has to be problematized in

accordance with the axioms and imperatives of the age of modernity on the one

hand and with Islam and political Islam on the other. Iranian secular

intellectuals insist on nationhood and modernity, while Islamists stress

Islamic notions. “If Iranian intellectuals in general, and scholars of Iranian

studies in particular, are to seek the correct answers to the question of

national identity, they must not imprison themselves in the torturous labyrinth

of arcane problematics, antediluvian ideas, ruminations of the past, mnemonic

conjecturing, and esoteric altercations. They need to realize that aversion to

new theoretical approaches, fetishization of the past, pompous bravado about

ancestors, conspiratorial and chiliastic views of history, and cult of

patriotism are futile strategies”.[61]

Political Islam has divided Iranians overseas and at home into two groups: radicals

who believe in Islamic government based on Shari‘a, and masses who live with

cultural Islam. Feeling nostalgia, like other Muslims, some Iranians might tend

to Iranian traditions or extremist groups. While Iranian/Islamic components (of

Iranian identity in the West) vs. the liberal one might be weakened in future,

Islamism and fundamentalism may possibly strengthened in some exceptional

cases.

[1] Robert Audi, The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy (Cambridge: University Press, 1999), p 415.

[2]SI has two schools of thought: the Iowa School and the

Chicago School. SI researchers in the Chicago School Chicago Iowa

School

[3] MKO is the abbreviation of Mujaheddin-e-Khalq Organization.

[4] For a comparison between political Islam and cultural Islam, see: Bassam Tibi, Islam between Culture and Politics, (Palgrave Macmillan, 2001).

[5] Mortaza Motahhari, Khadamat Motaqabel Iran va Islam (Cooperation between Iran and Islam), (Qom: Daftar Entesharat Eslami, 1983).

[6] Aramesh Doustar, Derakhshesh-ha-ye Tireh (“Dark Brightness”) (Paris, Khavaran, 1998).

[7] S.

Sadegh Haghighat, "Iranian Identity: a Discursive Analysis" (in

Persian), 3rd International Conference on Human Rights,

[8] See: Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger (eds.), The Invention of Tradition (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1983).

[9]Mehrzad Boroujerdi, “Contesting Nationalist Constructions

of Iranian Identity”, Published in Critique: Journal for Critical Studies of

the Middle East, no. 12 (Spring 1998); reprinted in Persian in Kiyan,

no. 47 (June-July 1999), pp 44-52.

[10] Mangol Bayat-Philipp, “A Phoenix Too Frequent: The

Concept of Historical Continuity in Modern Iranian Thought,” Asian and

African Studies, no. 12 (1978), p 203.

[11] David Marsh (and Jerry Stocker), Theory and Methods in political Science, 2nd Edition, (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002).

[12] M.Jorgensen (and L.

Phillips), Discourse Analysis as Theory and Method, (London,

Sage Publications, 2002).

[13] David Howarth , Discourse,(Open University Press, 2000), pp 105, 109, 113.

[14] Ernesto Laclau (and Chantal Moufee), Hegemony and Social Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics, p 105.

[15]Jorgensen

(and Phillips), Ibid, pp 26-28.

[16] . Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge and the Discourse on Language (New York: Pantheon Books, 1972), p 216.

[17] Edward Said, Orientalism, (New York, Vintage, 1979), pp 5, 235-237.

[18] Howarth, Ibid, p 22.

[19] Laclau, Ibid, p 51.

[20] Howarth, Ibid, 103.

[21] Jorgensen (and Phillips), op.cit, pp 41-43.

[22] Laclau, op.cit, pp 52-53.

[23]Boroujerdi,op.cit.

[24] Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, The Philosophy of History, (trans.) J. Sibree, (Buffalo, 1991,) p.173.

[25] Richard Nelson Frye, The Heritage of Persia, (London, Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1962), p 243.

[26] For instance, Yarshater has written the most eloquent statement of this view: “a more promising defense against the sense of anonymity that accompanies a submerged identity is a restorative and sustaining element that Persia has cherished and preserved against all odds: the shared experience of a rich and rewarding past. It finds its expression primarily through the Persian language, not simply as a medium of comprehension but also as the chief carrier of the Persian world view and Persian culture. The Persian language is a reservoir of Iranian thought, sentiment, and values, and a repository of its literary arts. It is only by loving, learning, teaching, and above all enriching this language that the Persian identity may continue to survive”: Ehsan Yarshater, “Persian Identity in Historical Perspective,” Iranian Studies, vol. 26, nos. 1-2 (1993): pp 141-142.

[27] See the following two works of Zabih Behruz, Zaban-e

Iran, Farsi ya Arabi?, (Tehran, Mihr, 1313 [1934-35]); and Khat va

Farhang, second edition, (Tehran, Furuhar, 1363 [1984-85]).

[28] Shahrokh Maskub, Iranian Nationality and the

Persian Language, translated by Michael C. Hillmann (Washington, DC, Mage

Publishers, 1992), pp 13, 31.

[29] Boroujerdi,op.cit.

[30] Seymour M. Hersh, the Iran Plan, The New Yorker (April 2006).

[31] Nayereh Tohidi, “Iran: regionalism, ethnicity and democracy”, http://www.opendemocracy.net/democracy-irandemocracy/regionalism_3695.jsp.

[32] Doustar, op. cit, p 43.

[33] Mirza Fath ‘Ali Akhundzadeh, Seh Maktoub (in Persian), (Paris, 1987), p 32.

[34] Maskub,op.cit..

[35] .http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Islamization_in_Iran

[36] Frye, op.cit, p 243.

[37] Motahhari, op.cit, pp 12-23.

[38] Said Hajjarian, “The Intellectual Currents in contemporary Iran”, Nameh Pazhuhesh, no 7 (winter 1998), pp 23-40.

[39] Shaul Bakhash, Iran: Monarchy, Bureaucracy & Reform Under Qajars: 1896 (London, Ithaca Press, 1978), p 19.

[40] Javad Tabataba’i, Constitutionalism in Iran (in Persian) (Tehran, Sotudeh, 2008), pp 11, 373.

[41] Mashallah Ajudani, Iranian Constitutional Movement (in Persian) (Tehran, Akhtaran, 2003), pp 198-199.

[42] Tabataba’i, op. cit. p 527.

[43] Javad Tabataba’i, Dibachee bar nazaree enhetat dar Iran (“An Introduction to the Deterioration Theory in Iran”), (Tehran, Negah-e Mo’asser,) 2001.

[44]

See Mahdiyeh Entezaekheir, “Why is Iran Experiencing Migration and Brain Drain

to Canada?”,

[45] Mostafa Moein, http://cdhriran.blogspot.com/2005_09_01_archive.html.

[46] .

Source:

[47] Source: US Department of State, Report of the Visa Office, 2000-2005.

[48] Ibid, and Shirin Hakimzadeh (and David Dixon), “Spotlight on the Iranian Foreign Born”, Migration Policy Institute, 2006.

[50] Tabataba’i, op.cit, p 102.

[51] Ajudani, op.cit., pp 424, 431.

[52] .Javad Tabataba’i, “My Project”, Iran Daily, (7-9/7/1382).

[53] For an analysis of conspiracy theories in Iran, see

Ahmad Ashraf, “Conspiracy Theories” in Encyclopedia Iranica, edited by

Ehsan Yarshater, vol. VI, fascicle 2,

[54] Said,op.cit..

[55] Bas de Gaay Fortman, "Islam and the West: the Sacred Realm, Domain of New Threats and Challenges", The 56th Pugwash Conference on Science and World Affairs, Egypt, 11-15- November 2006.

[56] Daryush Shaygan, Afsunzadegi Jadid (Ex Occidente Lux), Trans: F. Valiani, (Tehran, Farzan, 2001).

[57] Javad Tabatabaee, Zaval Andisheh Siasi dar Iran (“The Deterioration of Political Thought in Iran”), (Tehran, Kavir, 1994).

[58] Howarth, op.cit, pp 108, 121.

[59] Laclau, op.cit, pp 87-88.

[60] Paolo Bassi, “The Iranian Identity Crisis: Islam v.

Iranian Identity”, March 2006:

[61]. Boroujerdi,op.cit.